Dr Mark Wormald, Fellow and College Lecturer in English, writes: In May 2012 I stayed with the British-born Irish expressionist artist Barrie Cooke at his house and studio in County Sligo. I’d encountered his name in the fishing diaries Ted Hughes kept for the last 20 years of his life, and because I already sensed from those diaries, especially of their trips together in pursuit of Irish pike, salmon and trout, often with Ted’s son Nicholas, occasionally with Barrie’s youngest daughter Aoine, how deep their friendship was. That sense was confirmed on that first visit, but browsing Barrie’s bookshelves, I learned something new. The shelf below the one filled with every one of Ted’s books, personally inscribed to my host, was another, devoted to every one of Seamus Heaney’s books, again personally inscribed. If his friendship with the Hugheses turned on fish and fishing, his long and close friendship with the future Nobel Laureate depended, as Barrie told me, on ‘mud’.

On his death in 2014, his Irish Times obituary hailed Cooke as ‘an artist’s artist.’ Though his work features in the permanent collections of major European, British and American museums, that epithet can be mistaken, by those who are not artists, with faint praise.

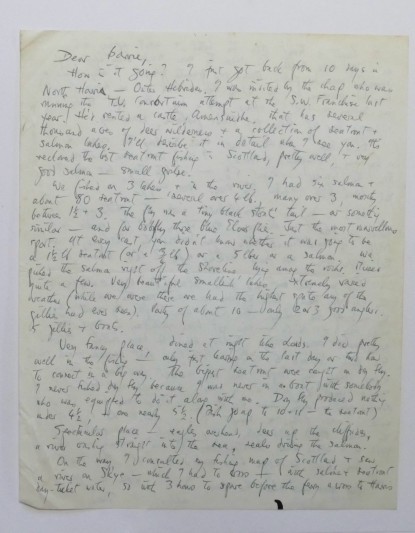

But as is evident in the extraordinary archive of letters, poems and other literary papers, which a grant from FNL was crucial in helping Ted Hughes’s Cambridge College acquire, Cooke was a poet’s artist too. Cooke cast a wry and often rapturous eye on his friends’ writing, producing some 150 charcoal drawings, monotypes, watercolours and lithographs of Hughes and Heaney’s poetry over a span of 35 years. Some were indeed of ‘mud’, yes: a remarkable limited illustrated edition of Heaney’s Bog Poems, published by Hughes’s sister Olwyn’s Rainbow Press in 1975, contained eight. Cooke painted 45. Heaney’s version of a medieval Irish epic ‘Sweeney Astray’ appeared in an American limited edition in 1984, again with eight small monochrome illustrations. Cooke produced 45, some wild, some delicate, some richly coloured. Heaney’s letter in delighted praise of them is one of the archive’s highlights; he wrote, elsewhere, of the combination of the distinctively Cookeish combination of la boue and beauté, ‘the muddy opulence of his palate’, and of Cooke himself as Ireland’s Green Man, a Sweeney for our time.

As for Hughes, Cooke illustrated Crow, and, in 1982, ‘The Great Irish Pike’, a suite of lithographs looming straight out of those Irish fishing trips with Nicholas, who also features in a sketch book full of images of the fish that haunted them all.

But Cooke’s full-blooded immersion in the wild and wet in Ireland’s natural and cultural history was infectious, inspiring Heaney, Hughes and others to send him poems (some never seen) and letters that are among their most expressive and transcendent. The painter’s guest book, also in the archive, reveals him as convenor of his own circle: a gathered cast of poets and artists to rival Bloomsbury, though they caught more fish. A record of great creative friendships across media and borders, the archive does not just crown Pembroke’s already unique collection of Hughesiana, established since 2012 with FNL’s help. The many warm responses to the public announcement in November 2020 of the acquisition of the archive include the donation of a hitherto unknown late poem by Hughes, with the touching story of the friendship that led to its composition, and a very significant collection of fascinating letters Cooke himself wrote to another leading Irish artist. As work continues on the cataloguing of the archive, in advance of its opening to researchers in 2021 and the first of a series of events and exhibitions on both sides of the Irish sea, it is already clear that this unique archive will change our understanding of the relationship between all these artists, and the shared creative passions that bound them.