In March 2020 the Britten-Pears Arts purchased the Archive of Lennox Berkeley Papers to form part of the Britten Pears Archive held at the Red House, Benjamin Britten’s home in Aldeburgh, Suffolk. The composer Lennox Berkeley was a great friend of Benjamin Britten and for a year they lived together in a house in the Suffolk village, Snape. They worked together to create the orchestral piece Mont Juic. Berkeley’s eldest son, also a composer, Michael Berkeley was Britten’s godson.

The Collection although held by the Britten Pears Archive was not owned by it, so it was not able to catalogue and share this impressive archive. The Foundation was, therefore, delighted to be able to raise the funds to purchase it and thus share it widely. The Collection contains manuscripts of Lennox Berkeley’s writings on music and musicians, his superb diaries, especially the diary from the 1960s, and the wide range of his correspondence. It comprises a rich resource for biographers and musical scholars but also for social and cultural historians. There are a fine series of letters from Britten and Pears and also an excellent group of about a dozen intimate and revealing holograph letters from Berkeley to Britten in which he writes of wartime London, his work as a voluntary air-raid warden, mutual friends, his own composition, the performance of his Introduction and Allegro at the 1940 Proms and much more.

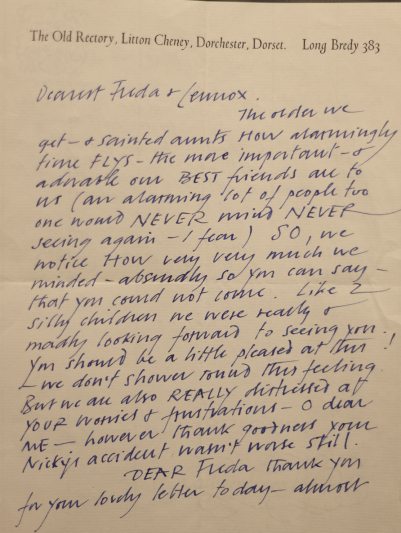

There are many dozens of correspondents within the papers revealing the range of Berkeley’s professional and personal friendships; these include Boris Anrep, Patrick Balfour (Lord Kinross), Conrad Beck, Arthur Bliss, Nadia Boulanger, Julian Bream, Diana Cooper, Laurie Lee (including a bound holograph manuscript of his four Signs in the Dark poems which he set to music), Julian Lloyd Webber, Yehudi Menuhin, John Nash, Sir Andrzej Panufnik, Desmond Shawe-Taylor, William Walton, Veronica Wedgwood, Malcolm Williamson and many others. The letters between Lennox and Freda Berkeley tell their own story and provide a solid documentary foundation for their individual lives, their marriage, and their friendships.

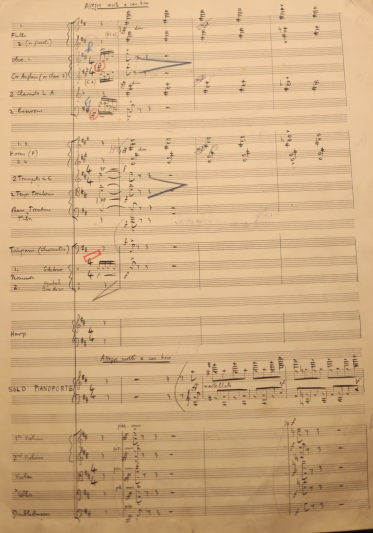

Of particular note the papers include the final fair copy score of Britten’s Concerto No. 1 in D Major for Piano Solo and Orchestra, composed for the 1938 Proms and dedicated to Lennox Berkeley, to whom the score was gifted. This is a particularly interesting manuscript for Britten scholars: the work was not published until after Britten had revised it in 1945 by replacing the entire third movement, so for some years this fair copy was the copy loaned to conductors for performance. As a result, this copy includes extensive annotation by various individuals involved in its performance, as well as copies of both the original and the new third movements.

As a musical and social history collection, the acquisition will be able to provide further information about the musical scene during the war and post war era. The letters alone provide a sense of the relationships Berkeley held. Significantly it will also mean that the Britten Piano Concerto score, such a valuable and central work within the Britten canon, is able to been seen alongside all the other material relating to its composition.