Eliza Howlett, Head of Earth Collections and Digital Collections Lead, writes: Oxford University Museum of Natural History (OUMNH) is enormously grateful for the support given by FNL towards the acquisition of this important archival collection. With over 1,000 items, the archive includes letters, notebooks, family papers and artworks relating to geologist and theologian William Buckland. A hugely influential figure in academia, politics, science and religion, Buckland was successively Reader in Mineralogy and Geology at Oxford University, Canon of Christ Church, Oxford and Dean of Westminster. He was the first to name and describe a fossil dinosaur (Megalosaurus) and his research into an ancient hyaena den laid the foundations of the science we would now call palaeoecology. He was also a notable convert to glacial theory, and showed how glaciation rather than a global flood shaped the British landscape.

The significance of this archive lies in the sheer breadth and depth of its subject matter. It reveals aspects of Buckland’s life as a student at Christ Church as well as his work as a practising geologist, university lecturer and eminent churchman, providing detailed insight into the thinking and institutions of the early 19th century, a time when science and theology often provided different explanations for natural phenomena. Numerous letters on a range of topics from zoology and geology to aesthetics and administration demonstrate the diverse network of people with whom he was connected, including major figures such as the art critic John Ruskin and prime minister Robert Peel.

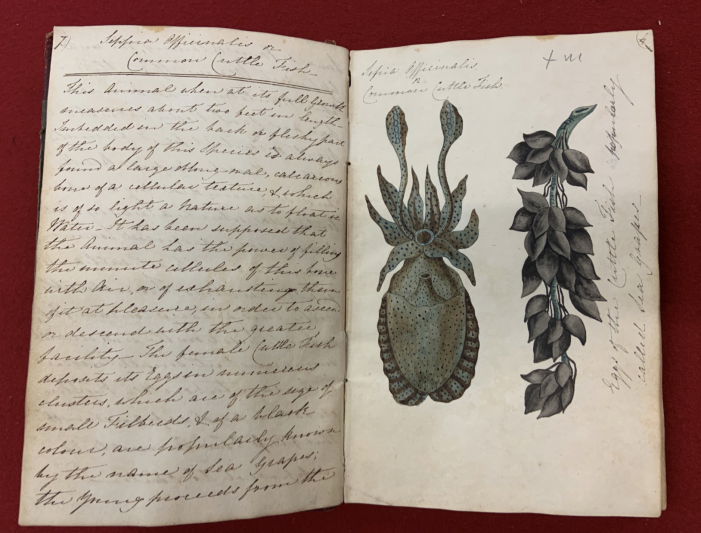

The archive also includes original artworks such as Thomas Sopwith’s watercolour of William Buckland (previously thought to be a portrait of Mary Anning), and a rare coloured version of the lithograph based on Henry de la Beche’s drawing Duria Antiquior, the first pictorial representation of a scene of prehistoric life based on fossil evidence. Excitingly, Buckland’s wife Mary (née Morland), a respected naturalist and illustrator, is well represented, with highlights including two of her sketchbooks. One of these, dating from before her marriage to Buckland, contains exquisite ink and watercolour drawings of natural history specimens and highlights the huge artistic and scientific contribution she made to her husband’s work.

OUMNH is already the pre-eminent repository for Buckland archive and object collections, with existing holdings including extensive professional correspondence, lecture notes and teaching diagrams as well as more than 5,0000 fossil, rock and mineral specimens. The interplay between specimens and archives is enormously powerful, and the acquisition of this additional family archive adds yet another piece of the jigsaw. Reuniting these collections both physically and digitally will allow researchers and other museum visitors access to the full spectrum of Buckland material, and adds significantly to our understanding of his life and work.