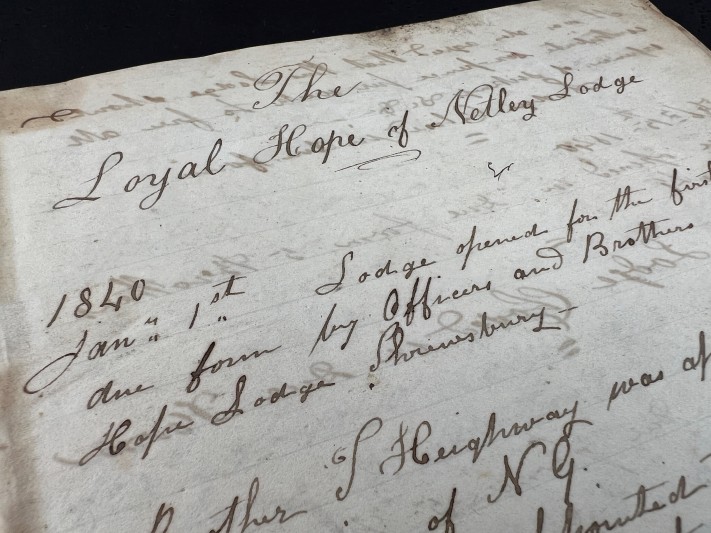

Sal Mager, Senior Archivist, writes: A rapid response from the Friends of the National Library to a request for funding enabled Shropshire Archives to acquire at auction the Loyal Hope of Netley Lodge minute book. Dating from when the Lodge was opened on 1 January 1840, the minutes chronicle 25 years of activity and provide fascinating insights into life in the local community.

Although the terminology used, referring to “Brothers”, “Grandmasters”, sashes, aprons and other regalia, suggests that the organisation was an official masonic lodge, there is no record of it as such. An entry referring to it as a “Sick Benefit Society” confirms that it was one of the numerous friendly societies that sprang up during this period, providing crucial support in times of sickness or other impediments to work. Apart from a couple of later financial documents, no other records are known to have survived from this particular lodge. It confirms how such societies were often closely modelled on their masonic counterparts. One entry of 1840 records how a past Vice Grandmaster was fined five shillings for “Disclosing the secrets of the order”. Other penalties imposed include a “brother” being “suspended from all Benefits of the Lodge for not paying for his Sash & Apron in Due Time”, a fairly common occurrence.

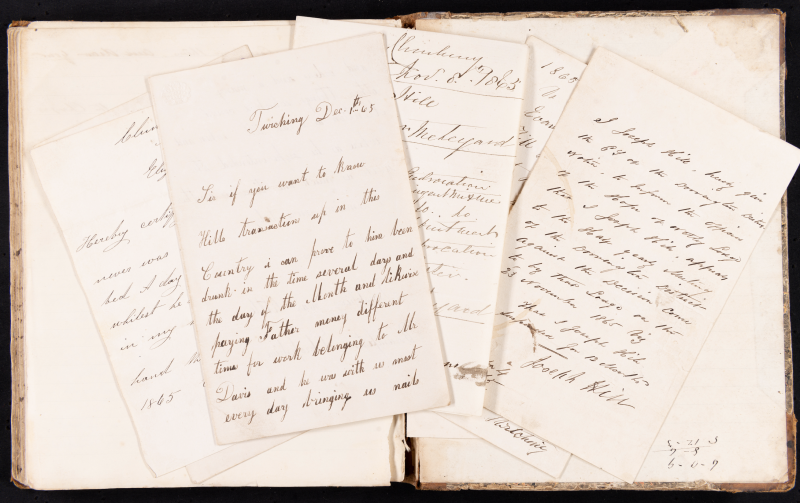

A particular value of the volume lies in its detailed first-hand accounts of interactions in the community, presented in the form of testimonies made during investigations into its members’ alleged misdoings. One witness relays how someone threatened to “knock my Head of[f] my shoulders if I said any more” when he caught one member digging in their garden whilst claiming to be ill. Landladies were said to exclaim “Lyeing old Monkey” and “Wicked Man to say such a thing” when told that their lodger had claimed to have been ill for three weeks.

One of the longest accounts records investigations into allegations of misconduct by Thomas Heighway, a former Provincial Grand Master of the Lodge, providing a fascinating insight into the intertwined relationships of family, personal and social life at this time. The accusation is that Thomas is “living in Adultery with a girl called Harriet Jones” along with her three children who it is claimed are his. The situation had been “talked on for years” but the recent action which caused “a great deal more talk” was Mr Heighway fetching them out of the workhouse to live at his father’s house. In his defence, Thomas pronounces that none of the children are his, claiming that he is supporting them on behalf of another man, whose name he has promised not to disclose. He finishes by saying “You had better send for the Girl and ask who is the Father of the Children”. Frustratingly, we don’t get to hear Harriet’s side of the story, although both her uncle and her brother testify claiming “she was a steady girl until Heighway cast his eye on her” and “he has been the ruin of her”. Nevertheless, it is unanimously agreed that Thomas is guilty of the charge against him and is to be expelled from the lodge.

The volume contains many more fascinating accounts of alleged misdeeds as the self-styled brothers and grandmasters of the lodge performed the role of judge and jury over those who were accused of acting with impropriety. We are grateful to be able to bring this manuscript into the public domain where it can serve to enrich the wealth of real life stories which local, family and social historians can draw upon.