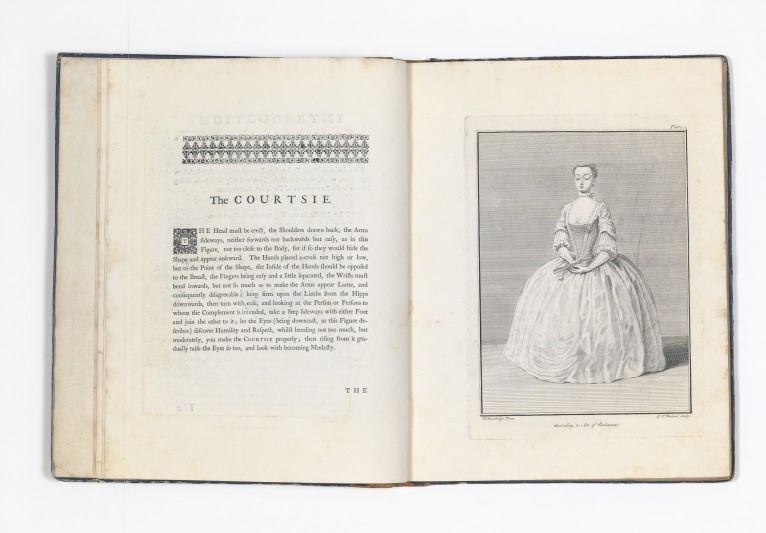

In the 18th century genteel behaviour was a crucial concern of London’s middling sorts, whose homes and domestic lives the Geffrye Museum represents. To be genteel encompassed, according to Johnson’s definition in 1755, both the notion of politeness in speech, and a more physical gentility – 'gracefulness in mien' – embodied in bearing and manner. The movements and expressions of the face and body were thought to reflect and direct the mind, and Nivelon therefore wrote to advise those 'who had rather be, and appear, easy, amiable, genteel and free in their person, mein, Air and motions, than stiff, awkward, deform’d, and, consequently, disagreeable’.

Nivelon would have been a familiar name and graceful figure to Londoners in the first half of the eighteenth century, he was a celebrated French dancer. No publisher is recorded on the title page of The Rudiments of Genteel Behaviour, and Nivelon is assumed to have overseen the production and commissioned the paintings and engravings himself.

The text and illustrations marry together precisely, and Nivelon uses both to repeatedly enforce the prescriptive nature of his advice.

The book, a wonderful addition in itself to the Geffrye’s library as a manual of genteel behaviour for the middling sorts, also enhances our understanding of these two paintings.