The acquisition of the Brownlee Jean Kirkpatrick’s archive of Virginia Woolf material was possible thanks to the support of the Friends of the National Libraries and the Carnegie Corporation of New York. It has greatly enhanced St Andrews’ strong holdings of literary manuscripts, which we make accessible for teaching and research at all levels.

The material was gathered by Brownlee Kirkpatrick (1919-2007), the bibliographer of Virginia Woolf, E.M. Forster, Edmund Blunden and Katherine Mansfield. Kirkpatrick was working as Librarian of the Royal Anthropological Institute in London when she undertook a bibliography of Virginia Woolf as 'one part of the University of London Diploma in Librarianship', which she completed in 1947 and revised in 1949. She consulted and gained the confidence of Leonard Woolf, who subsequently recommended her to the publisher Rupert Hart-Davis as Virginia Woolf's official bibliographer in 1951. The first edition of her Bibliography of Virginia Woolf was published in 1957, to be followed by revised editions in 1967 and 1980, and a fourth edition prepared in collaboration with Stuart Clarke in 1997.

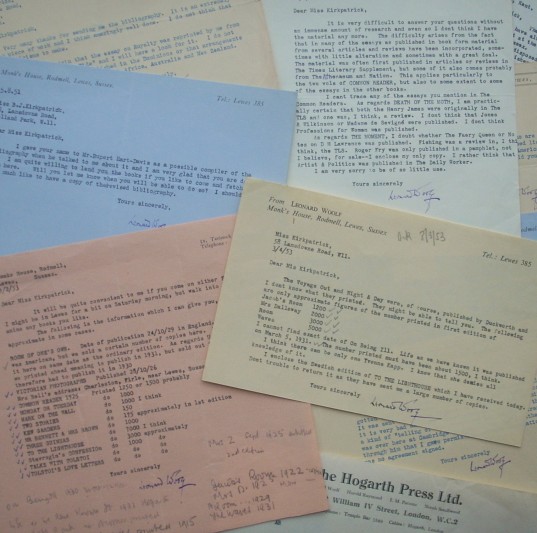

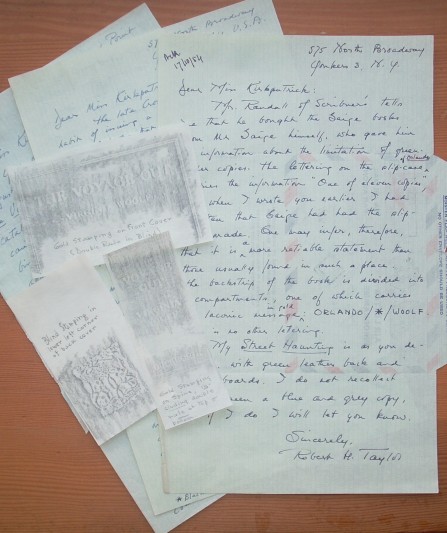

When Kirkpatrick began her research, many of those closest to Virginia Woolf were still alive, including her sister Vanessa Bell, Vita Sackville West and Leonard Woolf. All are well represented in the archive; Leonard most extensively in his 73 letters to Kirkpatrick which span two decades. Leonard Woolf's letters are wide-ranging and revealing, full of reminiscences about his late wife and their collaborations, of course dominated by the Hogarth Press. There are also two previously unseen photographs of Virginia Woolf taken by Leonard Woolf, which were given to Kirkpatrick as a possible frontispiece for her work. Leonard Woolf's biographer Victoria Glendinning has written about the strain he experienced in dealing with his wife's posthumous fame: 'The huge flow of correspondence - from academics, fans, researchers, bibliographers - began as a trickle as soon as she died, and would become a flood.' The collection reveals how Kirkpatrick's role as official bibliographer became a comfort to Leonard Woolf and brought her into contact with most of the surviving members of the Bloomsbury movement, including Vanessa Bell, Vita Sackville West, Harold and Nigel Nicolson, Quentin and Olivier Bell, John Lehmann, George Rylands and many others. A brief interlude in one of Kirkpatrick's letters to Olivier Bell makes clear the impact that he had on her bibliographical project: 'It could not have been done without Mr Woolf's unstinting help, which was given in so many ways. I did enjoy my visits to Monk's House, and returned to London with arms full of flowers, and in the summer with strawberries.'

The Kirkpatrick archive provides valuable information about Virginia Woolf's printed works, most from the Hogarth Press, but also provides much detail about the Bloomsbury group, allowing the reader to delve deep into what Victoria Glendinning has called Leonard Woolf's 'management of the past'. This archive is a splendid addition to the collections at St Andrews, and the value of the archive to Woolf scholars cannot be overstated.