The 38 letters of Robert Louis Stevenson to Anne Jenkin are published in the comprehensive Yale edition of his letters, but of the 15 which Fanny sent to Anne, only the heart-rending letter written the day after Stevenson’s death is known to be published. It is therefore in Fanny’s letters that the research value of the collection probably lies.

Anne was the widow of Fleeming Jenkin, Professor of Engineering at Edinburgh University. In that capacity he taught Stevenson, and though the latter showed little aptitude or interest in the subject, the two became close friends and Stevenson enjoyed visiting the Jenkin family in Edinburgh. Like Stevenson, the Jenkins were fond of amateur dramatics, and with their three young sons Stevenson must have been in his boyish element. Fleeming Jenkin died very suddenly in 1885 aged 52, and this correspondence begins when Anne asks Stevenson to write a memoir of her husband. A postscript to the earliest Stevenson letter in the collection reads ‘Dear me, what happiness I owe to both of you!’

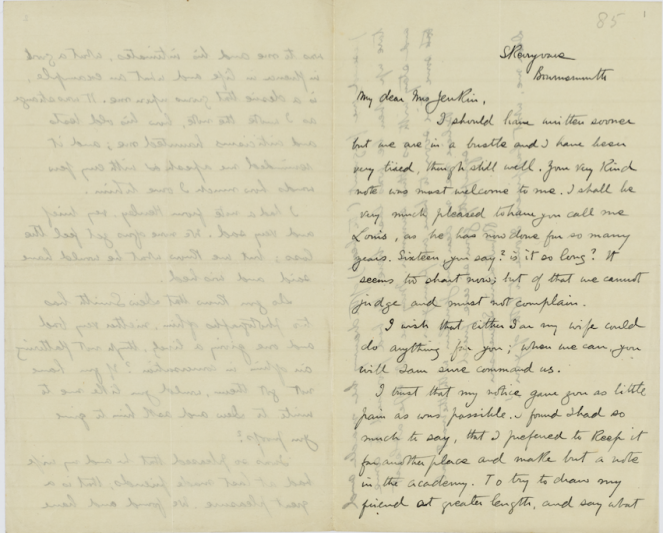

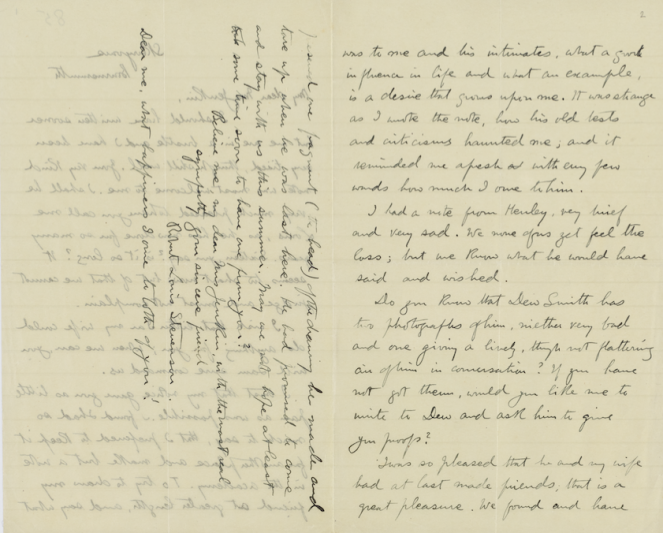

The writing of the memoir took the best part of two years. The letters to Anne reveal Stevenson struggling with ill-health, interruptions, writers’ block and his great desire to do right by his friend. He persistently questions Anne, who no doubt was glad of the involvement: ‘1st - When did Fleeming first see you? 2nd. Was he immediately in love? 3rd. When were you engaged?’ The letters are most frequent during the writing of the memoir, but an affectionate and thoughtful correspondence continued after its 1887 publication. In a letter of December 1892, Stevenson reassures Anne who is worried about her son making a bad marriage: ‘my marriage was largely in the teeth of what my parents wanted; they were deeply hurt … And now, as I look back, I think it was the best move I ever made in my life’.

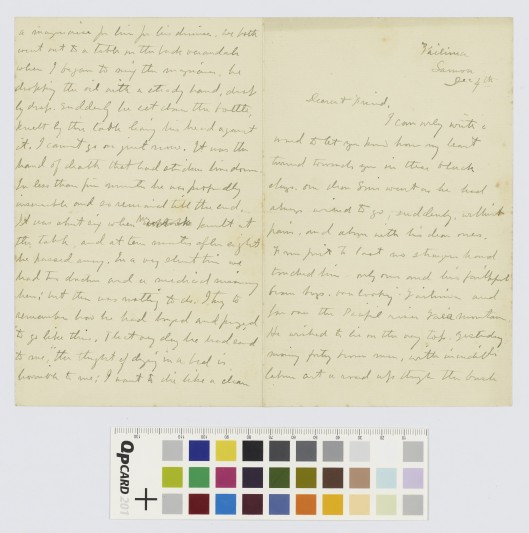

mso-ansi-language:EN">Back to Ginger … The Stevensons were preparing to leave for America in 1887, and Fanny in particular was anxious about the cat. Anne Jenkin evidently offered Ginger a home and, worrying in one letter about how to convey Ginger from Bournemouth to Edinburgh, Fanny asks ‘… would it be safe, do you think, to put him in a cage and send him by parcel post?’ By the next letter, Ginger is either en route or arrived and the fretful Fanny has moved on to instructions ‘I have only a moment which I shall devote to explaining about Ginger’. After more than a page of Ginger data, she writes ‘Louis is extremely weak, more so than he has ever been before, except when really ill in bed’. But Ginger was on his way, and the Stevensons would soon be sailing for America. Robert Louis Stevenson would never return to British shores.

The letters are now NLS Acc.13744.