The soke of Conisbrough was no single-village manor; centred upon its celebrated chief messuage Conisbrough Castle (notable for its place in Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe), this was a franchise initially made up of thirty townships scattered across the southern reaches of the West Riding. By the mid-14th century much of the lordship had passed into other hands, but 16 townships remained from that point until modern times.

In the hands of a succession of non-resident lords (including the crown) after the Warennes, earls of Surrey had died out in 1347, Conisbrough eventually became part of the estates of the Pelhams, earls of Yarborough in 1886. When the 5th earl died without a son it passed to sisters Diana (b. 1920) and Wendy Pelham as co-heiresses, whilst the rest of the Yarborough patrimony, including the earldom, passed to a cadet branch. By this stage, of course, the title lord of Conisbrough was an empty one, since what remained of manorial jurisdictions had been swept away by the Law of Property Act 1922, which abolished the copyhold tenure upon which the manor had been based. By the 1980s Diana, now Lady Miller, was housing the court rolls at her Doncaster residence. Their transfer to Doncaster Archives on long-term deposit was agreed in July 1982; after her death in 2013 her legatee chose to sell the manorial records and in 2016 invited Doncaster Council to purchase them. Thanks to generous grants from the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Friends of the National Libraries, they were acquired for Doncaster Archives in September 2017.

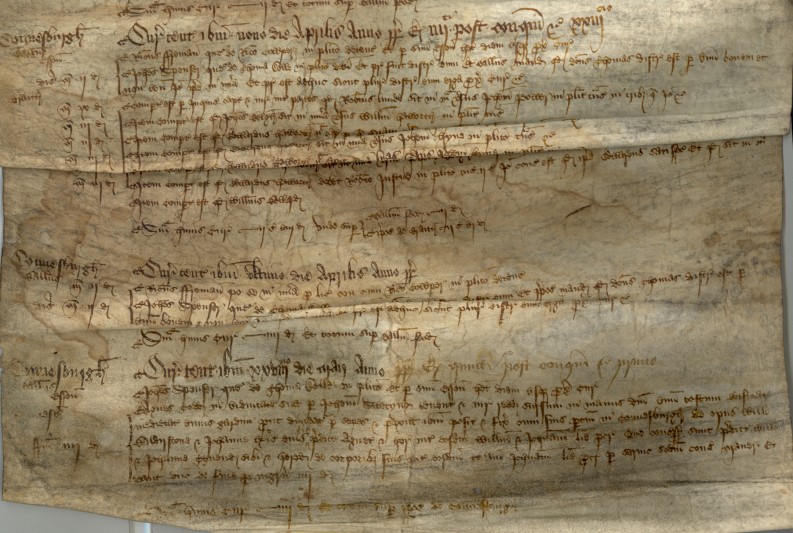

This is neither the largest nor the most complete series of manor court rolls, but it is exceptionally good, with 148 parchment rolls extant for the 368 individual accounting years between 1265-1266 and 1633-1634: a 40% survival rate. No more than four rolls represent the 13th century and there are only 21 from the 14th. Not a single roll remains from the admittedly short reign of Henry V, but thereafter the coverage improves. During this period the majority of the rolls consists of two or three membranes, although there might be as many as ten on occasion in the 14th century, prior to the alienation of a large part of the lordship. The membranes are characteristically all fastened together at the top (using thread or a parchment ligature) rather than with the foot of one membrane being stitched to the head of the next one. A roll of eight membranes carries the record for the ten years 1634-1644, whereafter the doings of the court during the Commonwealth are variously documented in a bound volume and an unusually large roll of sixteen membranes. Following a gap of forty years, for which the record is entirely absent, there is a final 17-membrane roll for 1700-1716. At this point the court roll ceases literally to be a roll and the remaining 218 years are covered by an unbroken run of fourteen volumes – latterly using paper rather than parchment. This change of format was almost contemporaneous with a change in the language of the record: English, experimented with during the Commonwealth, finally took over from Latin in 1733.

In the heyday of the court the rolls would have been kept secure in a muniment room close to the place where the court assembled. It was customary for manor courts to sit at the chief messuage of the lordship in question. After enclosure we find the business of the court being conducted at the offices of the solicitors variously appointed by different lords of Conisbrough to preside over what was left of the manor. The rolls were being kept by Messrs. J Archer & Son of Sheffield when the record agent J S Gibbons examined them in 1903. He later viewed the rolls at the premises of Messrs. Royds & Rawstorn, solicitors to the Earl and Countess of Yarborough, in Bedford Square, London, and there compiled the list that is still in use today.

To refer to the statutory protection afforded manorial records and to say that they provide a wealth of information about the interaction of ordinary country folk with each other and with the lowest form of local government is sufficient indication of their importance. It can also be noted that these records also represent a very neat fit with the so-called High Melton estate papers – purchased some eight years ago, also with generous assistance from the Friends of the National Libraries – since these are largely made up of the documentation of tenancies in the manor of Conisbrough held by the proprietors of neighbouring High Melton.