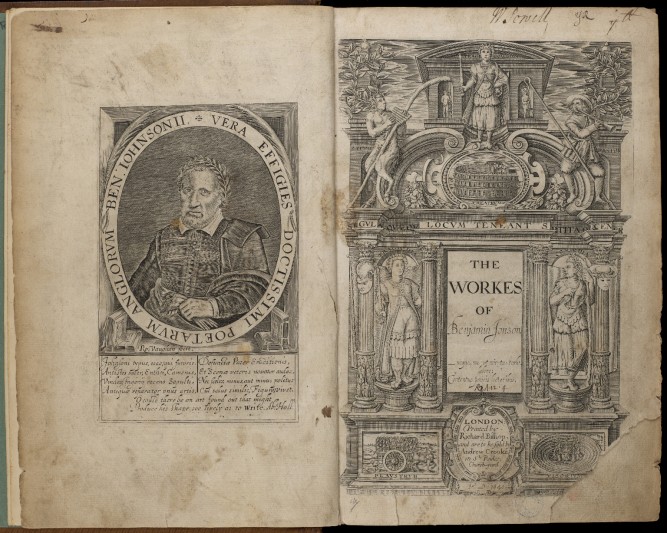

Ben Jonson (1572-1637) is arguably the most important writer of the English Renaissance after Shakespeare. His large and varied body of work includes plays, verse, court masques, entertainments, epistles, satires, translations, essays, epigrams, and a book of English grammar. In an age of great social change that produced some of the finest works of English literature, Jonson portrayed the cultural, social and political worlds in which he moved. As a man of letters, he was in close and sustained contact with the leading intellectuals and writers of his day. As a playwright, he was immersed in the theatrical world. As a writer for the court and aristocracy, he experienced at first hand the world of power. In addition, Jonson was the first writer to publish his own ‘Works’, an action which paved the way for the profession of author to be acknowledged as a distinct one.

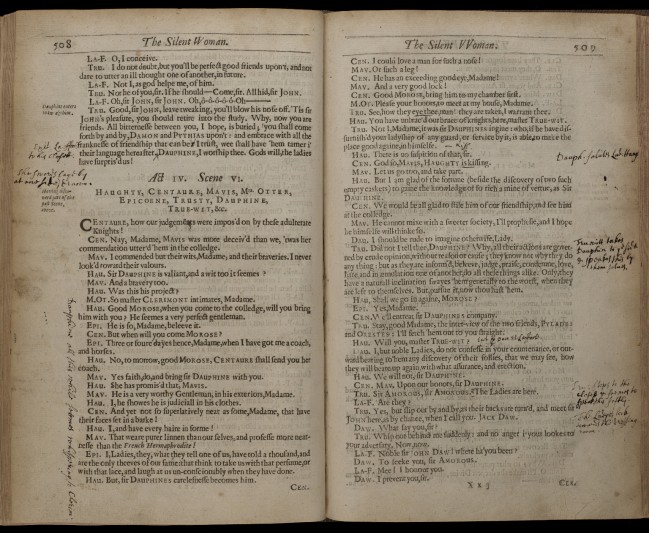

Epicoene is one of Jonson’s 17 plays, written and performed in 1609-10. Innovative for being a comedy which did not end in a marriage, it was not at first well received but it later achieved great prestige, being apparently the first play performed after Charles II re-opened the theatres in 1660. Following the Restoration, printed playbooks published before the Commonwealth were mined as a source of theatrical material, and manuscript annotations in the books can shed light on the way that these texts were repurposed for a different age. Only nine copies of pre-Restoration plays are known to preserve theatrical annotations. The volume has been found by the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art to meet the third Waverley criterion; that is, it is of outstanding significance for the study of English theatre in the 17th century and, in particular, for the study of Ben Jonson’s plays in performance.

Up until now, there has been no evidence of the preparation of any Jonson play, masque or entertainment for performance. Indeed, material which tells us about the performance of any pre-Restoration play is extremely scarce. This volume occupies a unique place among surviving materials because of the nature and range of its annotations, which collectively fall into no category yet known to scholars of 17th-century theatre. A product of a period when plays were seen not as finished pieces but as perpetual works in progress, this volume has the potential to change scholars’ understanding of how plays were transmitted from the stage to the page, and from the page back again to the stage.

The annotations, considered collectively, are unlike any that have ever been seen before in pre-Restoration playbooks. Annotators of plays for commercial performance constantly cut the text and did not concern themselves with performance details. Annotators of plays for amateur productions regularly cut the text and characters. Annotators of plays for the press made changes to the text itself. Here we see a new kind of annotator at work, one who is engaging minutely and precisely with the actors’ performance and who is beginning to enter into the fictive world of the play. Actors are instructed where to move and sometimes, with great subtlety, how to act (e.g. 4.1. ‘This Truwit must speak leisurly & observe every stop’; 4.5. ‘he feigns ye like to Dauph. Truwitt seems to unlock the door’). The presence or absence of each character on stage is meticulously recorded (prompt-book annotators, conversely, will record entrances rather than exits). Some annotations interestingly respond to the duration of the action. Small properties, not generally of concern to theatrical annotators, are frequently noted. Musical effects are added. Interventions to the dialogue are made to rectify inconsistencies; theatrical annotators, on the other hand, left dialogue text largely undisturbed.

The range of annotations means that this volume cannot be defined as a preparation copy (a survival which for a pre-Restoration play would itself be almost unknown) produced in advance of a fully completed prompt book. This volume will require a new edition of Epicoene; it will also be of great significance to Jonsonian scholarship, in particular to the study of the plays in performance and of Jonson’s posthumous reception. Further research will almost certainly be able to reveal more about the volume’s provenance and may well shed light on an actual performance. Was it a private production during the Interregnum, either in England or abroad? Was a production in the early Restoration being envisaged, perhaps a court performance which might call for greater elaboration than one for the stage?

The Friends of the National Libraries has helped to ensure that the volume will now be permanently preserved at Edinburgh University, where it can be made available for study and research.