Voyages to Madagascar; also, a history thereof during the reign of Radama and notes made on a voyage to the island of Mombassa in HM ships Phaeton and Andromache, 1817 and 1825 [manuscript].

Through the generosity of the Friends of the National Libraries the Foyle Special Collections Library at King’s College London has acquired an important first-hand manuscript account of an early British diplomatic and commercial mission to the kingdom of Madagascar. This 93-page bound volume is in the hand of Lieutenant Thomas Locke Lewis (c.1780-1852), a member of Britain’s 1817 mission to King Radama of Madagascar. Lewis tells the story of the mission and gives extensive descriptions of the island, its topography, climate, peoples and language.

In 1817 the Indian Ocean was an increasingly important stage for British imperial expansion, owing to its strategic value as the maritime route to Britain’s key imperial possession, India. During the wars with Republican and Napoleonic France Britain had made significant territorial gains in the region, acquiring such former French and Dutch possessions as the Seychelles in 1794, the Cape of Good Hope in 1806 and Mauritius in 1810. Britain wished to bring Madagascar within its sphere of influence and to reduce the risk of the island falling into the hands of a resurgent France in the future. Robert Farquhar, governor of Mauritius, therefore despatched a diplomatic and commercial mission to Madagascar in 1817, with the aim of securing King Radama’s allegiance. Radama would pledge to abolish the slave trade and to permit British missionaries to practise on the island; in return the British would provide military and financial support and would recognise him as the island’s sole ruler. The mission’s leader was former army officer James Hastie, who, as a result of the formal treaty of alliance made with Radama on 23 October 1817, remained in Madagascar for the rest of his life, occupying the position of civil agent for Britain and de facto ambassador.

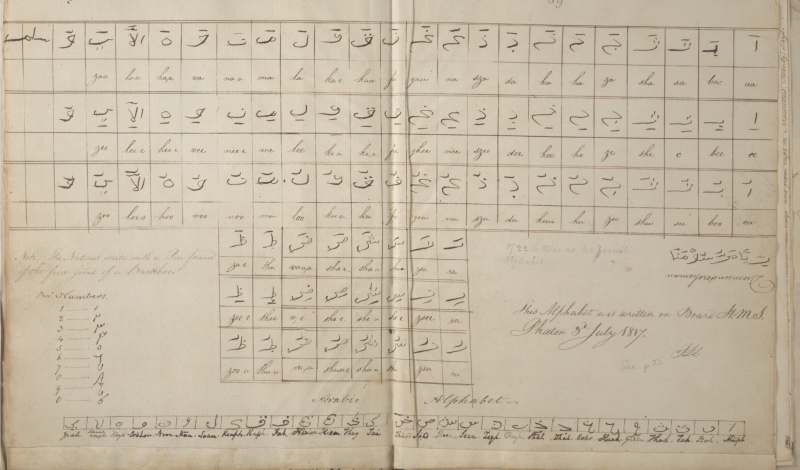

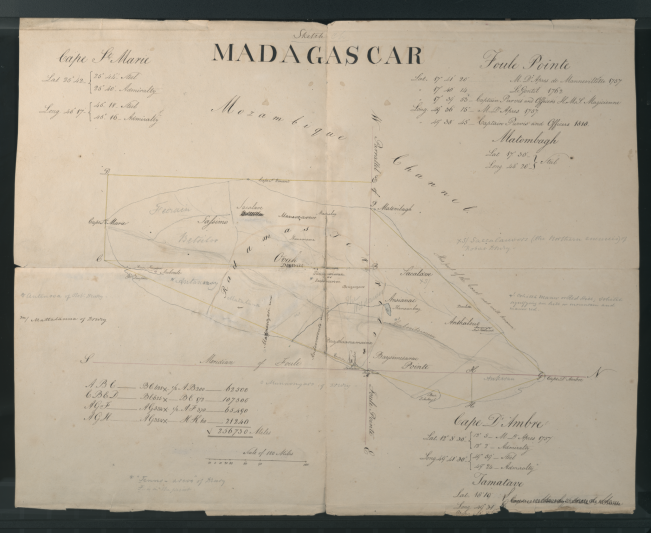

The manuscript’s value lies not only in the wealth of detail it provides about this otherwise little known episode in British diplomatic history but also in Lewis’s copious observations on the island of Madagascar itself. A sketch map of the island is one of the earliest to contain demographic information and Lewis also included geodetic data, enabling him to calculate the size of this huge land mass. A fold-out map of the harbour of Tamatave is possibly the earliest cartographic representation of this port. Lewis appears to have been particularly interested in the languages of Madagascar and the manuscript includes an Ovah alphabet.

Andrew Lambert, Laughton Professor of Naval History at King’s College London, comments: ‘This [manuscript] is a very significant addition to the limited archival resources that support scholarship on British and French policy towards the Indian Ocean islands in the Napoleonic era, a subject that has long needed academic attention’. The manuscript’s potential value for teaching, research and wider engagement is considerable. The Library runs teaching sessions with Dr Kai Easton of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) for its MA in African Studies and BA module on ‘Southern Spaces’. These sessions include a focus on Madagascar and the Indian Ocean islands, and Dr Easton has described the Lewis manuscript as potential ‘required reading for generations of young scholars’. On the research side, there is a keen appetite for the preparation and publication of a scholarly edition of the manuscript, containing a facsimile, transcription, notes and introduction, and we hope that one or more PhD researchers may work on such a project. Finally, there is scope through digitisation for fostering links with Madagascan scholarly, cultural and official bodies.