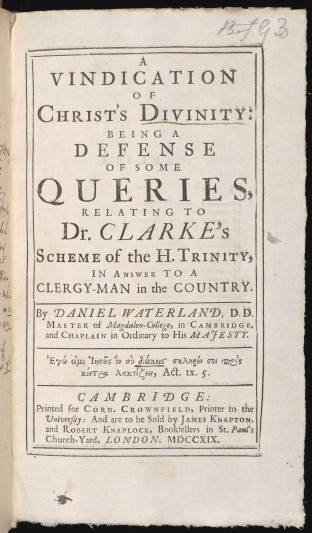

Liam Sims, Rare Books Specialist, writes: Daniel Waterland was the most influential early 18th-century teacher of divinity in the University of Cambridge and the most significant defender of the doctrine of the Trinity, masterminding attacks on Clarke and later Sir Isaac Newton. His Vindication was an important step in the long-running debate set off by Clarke’s Scripture-Doctrine of the Trinity (1712), itself part of the even longer-running dispute over the historicity and veracity of the doctrine of the Trinity, which might be viewed as the defining controversy for the 18th-century Church of England.

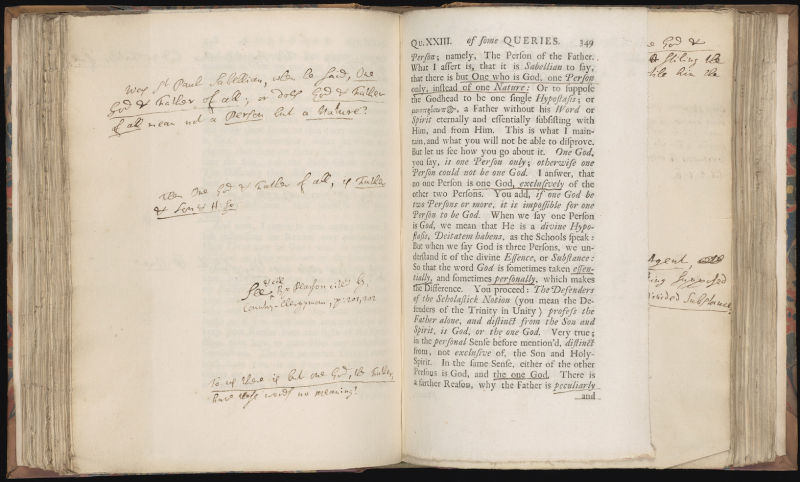

This copy of his Vindication is interleaved, and heavily annotated by Samuel Clarke (1675-1729), a student at Gonville & Caius College Cambridge in the 1690s, Fellow of the Royal Society, and a friend of Newton (Clarke was responsible for the translation of the 1706 Latin edition of Newton’s Opticks). This copy is undoubtedly the one that Clarke referred to in a letter of 2 June 1719 to his collaborator, John Jackson (1686-1783), and printed in Memoirs of … John Jackson (1764): ‘I have interleaved W[aterlan]d, and am making short Notes for you throughout.’

Waterland’s response and Clarke’s annotations range across six years of controversy and look forward to a further decade of future argument. Clarke’s annotations helped Jackson to compile the rebuttal of Waterland that he published in 1722 (A Reply to Dr Waterland’s Defense of his Queries), itself the first of three works published over a period of two years. At the heart of the debate is the question of the use of what Clarke and Jackson call ‘metaphysical’ language in divinity, a topic that Clarke also touched on in his famous exchange with Leibniz (A Collection of Papers, 1717), which is referenced in the manuscript annotations made in this volume. Clarke’s rejection of philosophical metaphysics and his defence of the critical presentation of scriptural terms for divinity has much in common with the ideas of Newton. Given the correspondence between Jackson and Clarke, it is interesting to note how different the emphasis of the annotations in this volume and in Jackson’s later printed response are. Clarke’s extensive annotations are a stage in the composition of a controversy: they are neither quite instructions to an amanuensis nor drafts for a published text of the author’s own. As such, they reflect very particularly on Clarke’s own role in and reactions to a controversy that he largely sought to conduct in public through proxies.

These fascinating volumes are the most interesting copy possible of an important work of early 18th-century Cambridge theological controversy, revealing much about the management of a printed controversy of great intellectual and institutional importance in the early 18th century. The notes are unknown to past writers on Samuel Clarke and represents as substantial a surviving body of his work in manuscript as can currently be found.