Tim Procter, Collections & Access Manager, writes: Unknown and thought to be unpublished, this 112-page vellum-bound manuscript was written probably around the 1580s. The manuscript, in Secretary hand, is probably the first comprehensive academic study of a single foodstuff to be written in the English language, which gives it particular significance for food historians. Although cheese has formed part of the human diet since the introduction of farming in the prehistoric periods, there is little early evidence of its character and places of production in Britain except for entries for anonymous cheeses in household accounts. It also gives a unique insight into the food habits of the general population, as the author visited several localities and talked to locals making cheese as part of their survey.

The author is currently unknown, but it is hoped that further research will uncover their identity. However, the manuscript passed through some influential hands. It was circulated in the group around the Dudleys, the family of courtiers whose influence throughout the Tudor period was at a peak around the time of the manuscript’s creation. In a note on the flyleaf, Clement Fisher, MP for Tamworth, asks for the book to be returned to him when it has been ‘perused’; Walter Bayley, whose name appears at the end of the text, was Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford and physician to Elizabeth I; and Edward Willoughby of Bore Place, Kent, came from another family of parliamentarians.

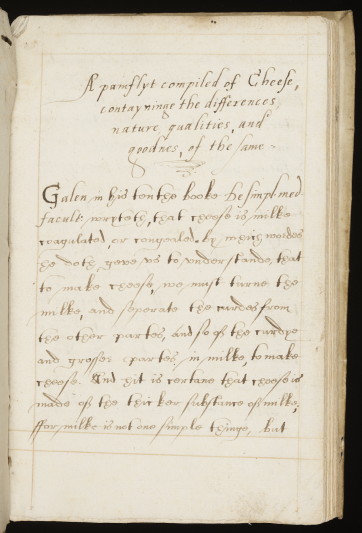

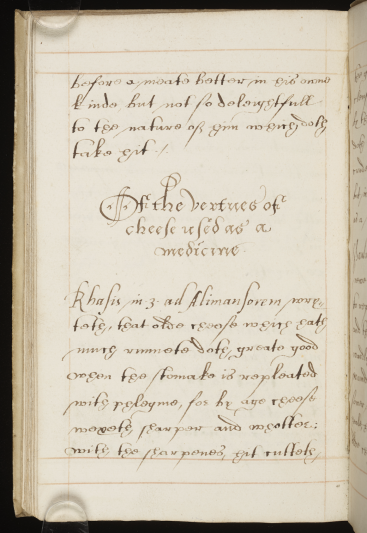

The ‘Pamflyt’ follows typical Elizabethan practice of collecting all available information from Classical authors such as Galen and Virgil - it opens with the Greek philosopher-physician Galen’s broad definition of cheese as ‘milke coagulated, or congealed’ - as well as the Persian philosopher-physician Abu Bakr al-Razi, and contemporary physicians at the University of Salerno. There is also a section on ‘the vertues of cheese used as a medicine’, with the effects of cheese on people of different temperaments based on the theories of the bodily humours put forward by Galen and his predecessors.

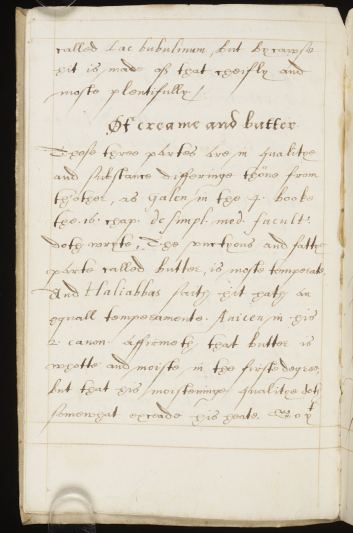

To gain practical information, the author then went on to ‘diligently inquire of country folke, who gave their experience in theis matters.’ The text discusses subjects including curds (‘or cheesye partes of milke’) and whey; and the many different cheeses found throughout England and Wales, their ingredients, methods of production and merits. The author makes several regional observations, for example that butter was currently being made from ‘boiled milk’, in other words, clotted cream, a practice that was still followed in the West Country well into the 20th century, or that most Welsh cheeses were made of mare’s milk, some adding goat’s milk. The best British cheeses were Banbury and Cheshire, followed by Llanthony and Caerleon, later known as Caerphilly, from Wales.

The ‘Pamflyt’ will join the Cookery Collection at University of Leeds Libraries, one of the great assemblies of printed and manuscript material relating to domestic science. Blanche Legat Leigh presented her collection of 1,500 printed cookery books and manuscripts to Leeds in 1939, and the collection was greatly enhanced in 1962 by John F. Preston, who donated 600 British cookery books printed before 1861. The Chaston Chapman Collection added an extensive library of books on brewing and the brewing industry, wine and winemaking, and drinking customs. Its holdings continues to grow, with the acquisition in the 1980s of the Camden Library cookery collection covering the later 20th century, and the arrival of the library of the food writer and journalist Michael Bateman in 2011.